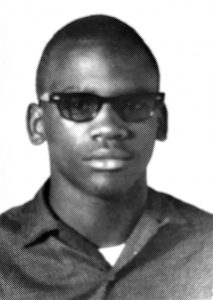

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, granting equality and integration in schools, the Rev. Anthony Mays became the first and only African-American student to be allowed to enroll in Round Rock High School for the 1964-1965 school year.

Mays, now senior pastor at Mount Sinai Missionary Baptist Church in Austin, attended Hopewell Negro School until his sophomore year when he enrolled at Round Rock High School, located at what is now C.D. Fulkes Middle School. Mays registered with Principal C.D. Fulkes in September 1964, becoming the model for integration in Round Rock.

“I was nervous because I was in an environment that I had never been in before,” Mays said. “I didn’t have any friends, I didn’t have anyone that I actually knew. I did make friends and become known, but when I first started, I didn’t know whether I would be accepted or not.”

A 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, ruled the segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Despite the decision, many southern states, including Texas, did not accept the ruling as law, according to Tina Melcher, (former) Round Rock ISD K-12 social studies curriculum coordinator.

Following the Civil Rights Act of 1964, some southern school districts were still not in compliance, prompting United States v. Texas, which tasked the Texas Education Agency to enforce the desegregation of schools, Melcher said.

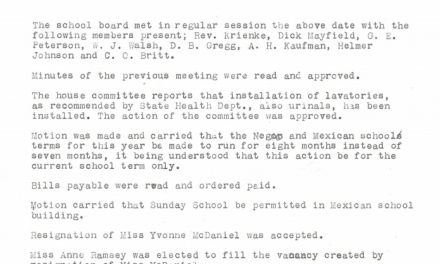

School integration was first discussed at Round Rock ISD in August 1963, but since two Board members were absent no policy was formulated.

Board Minutes from the August 13, 1964 meeting simply stated, “On a motion and second by Conrad Zimmerman and Ray Woytek and unanimous vote of the board full compliance with Civil Rights Act, Pulbic [sic] Law 88-352 88th Congress, H.R. 7152, July 2, 1964 was approved – to be effective immediately. (Two high schools are to be continued with free election of students as to which school they attend.)

Full desegregation at all grade levels was approved March 1966.

“I appreciate the fact that we have records to describe our history,” Melcher said. “This is a great teaching moment for our students as we move forward as a community and prepare the next generation of leaders.”

Mays was the sole African-American student at Round Rock High School for two years until Hopewell Negro School closed in 1966 and the schools were fully integrated. During his first two years at Round Rock, Mays was determined to be a positive example for African-Americans because he was the first African-American person many of the students had encountered, he said.

“Because there were not a lot of instances where I interacted with white people, I didn’t know anything about them and many of them didn’t know anything about me,” Mays said. “It was really good that we got to know each other as people instead of hearing stereotypes of what people were like.”

Mays was a devoted student and athlete, which, he said, helped with the integration because the students could see him as a teammate and friend.

Mays graduated in the top 10 percent of the Round Rock High School class of 1967, was a member of National Honor Society and was named a finalist for Outstanding Negro Students National Merit Scholarship, he said. Because of his opportunities at Round Rock High School, he was able to earn enough credits to enroll in the University of Texas at Austin where he graduated with an English degree.

“I am thankful for the cooperation of my community and the support of leaders and administrators for how the transition occurred,” Mays said. “It wasn’t very dramatic. There wasn’t anyone standing in the door saying you cannot enter. It was just smooth.”